Sep 03, 2025

Jordana A. & Simon L.

6min Read

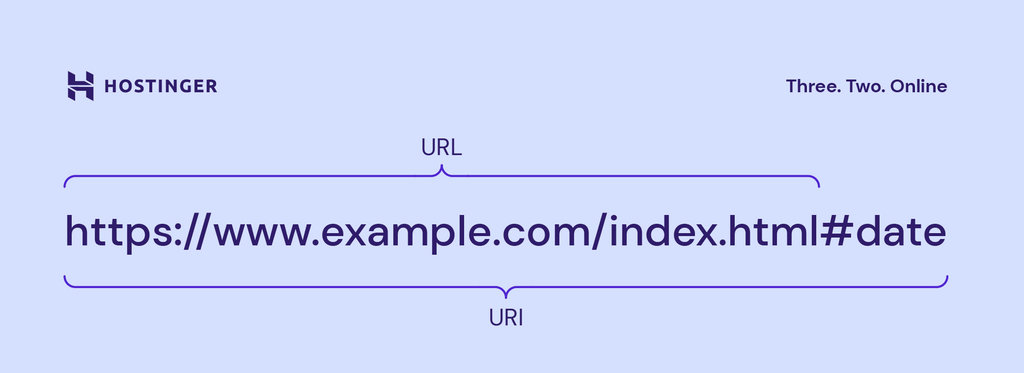

A URI, or Uniform Resource Identifier, is a way to identify any resource online, such as a webpage, a document, an image, or something else entirely. Think of it as a unique ID. This identification can be based on the resource’s name, its location, or both.

A URL, or Uniform Resource Locator, is a specific kind of URI. It identifies a resource and also tells you exactly where to find it and how to get there. It includes the access method, like https:// and the address of the resource on the web, like www.example.com/page.

Here’s a quick breakdown of the main differences.

| Category | URI (Uniform Resource Identifier) | URL (Uniform Resource Locator) |

| Purpose | To identify a resource by name, location, or both. | To locate a resource by specifying its access method and location. |

| Relationship | The superset of a URN and a URL. | The subset of URI. |

| Syntax | Contains components like a scheme, authority, path, and query. | Has similar components to a URI. Its authority consists of a domain name and a port. |

| Example | ISBN 0-476-35557-4 | https://hostinger.com |

| Common use cases | Usually used in XML, tag library files, and other files, such as JSTL and XSTL. | Mainly used to search web pages on the internet. |

| Scheme definition | URI scheme can be a protocol, a specification, or a designation like HTTP, file, or data. | URL scheme is a protocol, such as HTTP and HTTPS. |

The key distinction is that every URL is a type of URI, but not every URI is a URL.

Think of it like this:

The main difference is that a URL specifies the protocol and the location of a resource, whereas a URI can identify a resource by name, location, or both.

Here’s a breakdown of what that means in practice:

While both share a common structure, a URL has stricter syntax rules and must contain specific components to be valid.

Here’s how the syntax compares:

This is the first part of the address that ends with a colon, like https: or mailto:. It tells the computer what it’s dealing with.

This is the part right after the // that usually contains the website’s domain name, like www.hostinger.com.

This part comes after the domain and looks like a folder path on your computer, such as /tutorials/uri-vs-url. It pinpoints the exact page or file you want on that website.

This optional component starts with a ? and is used to send extra information, like ?search=how-to-build-a-website. Think of it as adding a filter to your request.

This is an optional part that begins with a #, like #section-2. It tells your browser to jump directly to a specific part of the webpage, so you don’t have to scroll to find it.

Knowing when to use each term depends on what you’re trying to accomplish.

Use a URL when you need to access a resource on the web. This is the most common use case.

If you’re putting an address in a browser, linking to a page in your HTML, or calling an API endpoint, you’re using a URL. It provides the complete address needed to retrieve something.

Use a URI when you need to uniquely identify a resource, regardless of its location. This is more common in technical contexts.

For example, in XML or RDF files, a URI can act as a unique name for a data element or concept. Instead of pointing to a webpage, it just needs to be a unique identifier.

Ever wondered what each part of that address actually does? Our detailed guide on what a URL is breaks it all down.

Let’s look at how URIs and URLs are applied in different scenarios to make the distinction clearer.

URIs are used to assign unique serial numbers to creative works. This allows them to be identified in databases and catalogs without pointing to a specific file online.

For example, an ISBN (International Standard Book Number), like urn:isbn:978-0321765723, uniquely identifies a specific book but doesn’t tell you where to find it online.

Similarly, an ISAN (International Standard Audiovisual Number), like urn:isan:0000-0004-87D7-0000-Q-0000-0000-6 can identify a movie without providing a link to watch it.

The tel: scheme creates a URI that identifies a telephone number.

For example, tel:+1-816-555-6666 is a globally unique identifier for a phone number. It doesn’t refer to a physical device but simply names the resource.

This is the most common use case. When you type an address into your browser or click a link, you’re using a URL to navigate the internet.

These are often absolute URLs, containing the full protocol, domain, and path, like https://www.hostinger.com/tutorials/uri-vs-url.

URLs can also appear without a protocol and domain, specifying only the path. Known as relative URLs, they link to a file within the same website.

For example, the relative URL for the page above would simply be /tutorials/uri-vs-url.

In API development, endpoints are represented by URLs. For instance, https://api.example.com/users/123 is a URL that allows an application to interact with the data for user 123.

Search engines like Google crawl and index URLs to understand a website’s structure and content. Clean, descriptive URLs are a best practice for helping both users and search engines.

A URL can specify an email address using the mailto: scheme, such as mailto:abc@example.com. Clicking this link on a webpage typically opens your default email client.

URLs are crucial for redirecting users from an old page to a new one. For example, if a blog moves from blog.example.com to example.com/blog, a redirect ensures that users accessing the old URL are automatically sent to the new location, preventing 404 errors.

URLs can use protocols other than HTTP. For example, the telnet://192.0.2.16:80/ URL is used to connect to a remote computer at a specific IP address and port, often for troubleshooting servers.

The relationship between URI and URL is hierarchical. URI is the parent category, and URL is one type of URI.

Think of it like this:

Both a home address and an ID number are forms of identification, but they serve different functions. Every URL provides a location, making it an identifier. But not every identifier provides a location.

It all depends on what you’re trying to do. If you’re linking to a webpage, a stylesheet, or an image online, you’re using a URL.

If you’re a developer defining a unique identifier for a piece of data in a schema that won’t be accessed over the web, you’re using a URI.

In practice, unless you’re a developer, a URL is what you will use for almost everything you do online. It’s the locator for all the resources we need when browsing websites or developing them.

The heart of every URL is its domain name. To get the full picture, check out our guide on what a domain name is and how to choose the perfect one.

All of the tutorial content on this website is subject to Hostinger's rigorous editorial standards and values.