Jan 07, 2026

Larassatti D.

12min Read

Jan 07, 2026

Larassatti D.

12min Read

AI browsers are the latest result of the shift toward agentic AI. They can summarize content, compare products, check out items, fill forms, and even complete multi-step tasks with a single instruction. It’s a big upgrade in convenience compared to traditional browsing.

But to reach this level of automation, AI browsers introduce a new set of privacy, control, and security trade-offs that most people haven’t had to consider before.

Compared to other, more commonly used generative AI tools, AI browsers occupy a position within a digital infrastructure, operating in a gray area where privacy expectations, security safeguards, and industry standards have not yet caught up.

AI browsers can also act autonomously, so they can unintentionally expose sensitive data, misread your intent, or take actions you never meant to authorize.

Before you decide to rely on an AI browser, it’s worth understanding what they actually do, what issues still exist today, and what trade-offs you’re agreeing to.

OpenAI’s Atlas and Perplexity’s Comet represent the first wave of AI-native browsers that treat the browser as an active agent rather than a passive viewing tool. They share one technical similarity: they’re built on Chromium, the open-source engine that powers Google Chrome.

This explains why opening any AI browser immediately feels familiar. The tab interface, address bar behavior, bookmark systems, and developer tools closely resemble Chrome because they share the underlying architecture.

Google Chrome with Gemini and Microsoft Edge with Copilot have added AI capabilities in response to the release of these AI browsers. However, these remain features layered on top of traditional browser frameworks.

AI-native browsers, such as Dia, Comet, or Atlas, design every component with AI processing at its core. The browser continuously analyzes content, interprets your goals, and determines how to help before you ask. If the AI function is removed, they’ll just be a non-functional shell.

Meanwhile, AI-enhanced browsers, such as Google’s Gemini in Chrome or Microsoft Edge with Copilot, are built on top of traditional browser architectures. The underlying browser works precisely as it always has – AI provides optional assistance when you activate it.

These tools all approach the problem differently, but they represent the same underlying shift toward browsers that actively interpret, summarize, and act on your behalf.

Note that we won’t be comparing feature lists in the following sections. Instead, we’re going to look at the broader architectural model, the risks it introduces, and what this new class of software means for users in general.

And if you want to explore more AI browser options, you can check out our Hostinger Academy video:

For the last thirty years, web browsers have mostly been passive viewing tools. While they offer features like password managers and autofill form inputs, they can’t assist with complex tasks.

The “magic” of the emerging AI browser ecosystem is that it’s moving from a tool that displays the web to an active agent that understands it – meaning that it can actually assist you with complex tasks.

Instead of digging through menus and remembering where to find a specific setting, you can simply tell an AI browser what you want to do. It’s less about clicking buttons and more about stating your intention, all in your own plain language using the in-browser command bar.

Instead of scrolling around to find the “Print to PDF” option, you only need to type, “Save this receipt to my Finance folder.” The browser understands what you mean and does the actions – exactly as you would ask a personal assistant to do something for you.

AI browsers reduce the need for constant switching between tabs.

Researching something online with a conventional browser can lead to tab overload. You open one tab to compare products, another to check details, and another to look up related topics – then keep switching between them to find what you need.

Instead of clicking back and forth or spreading them across multiple windows, AI browsers can synthesize information across tabs into a single view. All you need to do is have all the tabs open.

For instance, you’re checking the flight schedule in one tab, looking at hotel locations in another, and reviewing your calendar in a third. On the side prompting panel, you can ask AI to create a list of the best holiday schedule options with the lowest flight price and the most convenient flight time.

Standard browsers store data, such as history, cookies, and autofill, by default, but they don’t retain an understanding of your goals, context, or ongoing tasks.

AI browsers flip that idea. They keep a memory of the things you browse.

If you spend Monday looking for hiking boots, the browser notes your size, what brands you like, and whether you need waterproofing. When you return days later, even to a completely different website, it uses that knowledge to filter results automatically.

Instead of starting from zero every time, the browser keeps your context alive. It becomes less like a browsing tool and more like an extension of your own long-term memory.

AI browsers also change how we process information – they don’t just summarize a long article, but they can also pull ideas together across different sources.

An AI browser can watch a YouTube video and jump to a specific timestamp you need, skim three articles that disagree with each other, and read a Reddit thread, then combine all of that into one clear explanation. The browser stops being a firehose of information and becomes a filter that gives you the essence, delivering clarity straight to you.

The widely known generative AI products, such as ChatGPT, Claude, or Perplexity, are built using large language models (LLMs). They can explain, summarize, answer, and reason, but they can’t perform any actions. When an LLM helps you “book a hotel,” it generates text instructions that you still have to execute.

AI browsers integrate large action models (LAMs) on top of that, enabling them to create actions. A LAM can observe a webpage, understand its structure (buttons, fields, menus, flows), and interact with it on your behalf.

Instead of you searching for a restaurant, checking availability, and filling out the booking form, you can simply say, “Book a table for two in a fine dining restaurant at 7 PM.” The browser then sends out an AI agent that clicks the buttons, fills the form, and handles everything behind the scenes.

AI browsers can only bring convenience by gaining visibility into what you click, what you read, and what you return to. Just like training a new personal assistant you hired, they can do the job well if they have enough context.

To ensure the generated outputs closely match your preferences, AI browsers incorporate a memory layer. Even when this memory lives locally on your device, the AI still remembers patterns of your behavior unless you explicitly wipe that memory.

However, as stated on Atlas’ Data Controls and Privacy page, deleting your browser memory means all of your browsing convenience will also be wiped. Once you do that, it’s like firing your experienced personal assistant and having to train someone new from the ground up.

Also, note that clearing history doesn’t necessarily equal clearing up understanding. It’s possible to delete the logs while the preference models remain intact, mainly if the AI uses embeddings or local vector databases to build a profile of what matters to you.

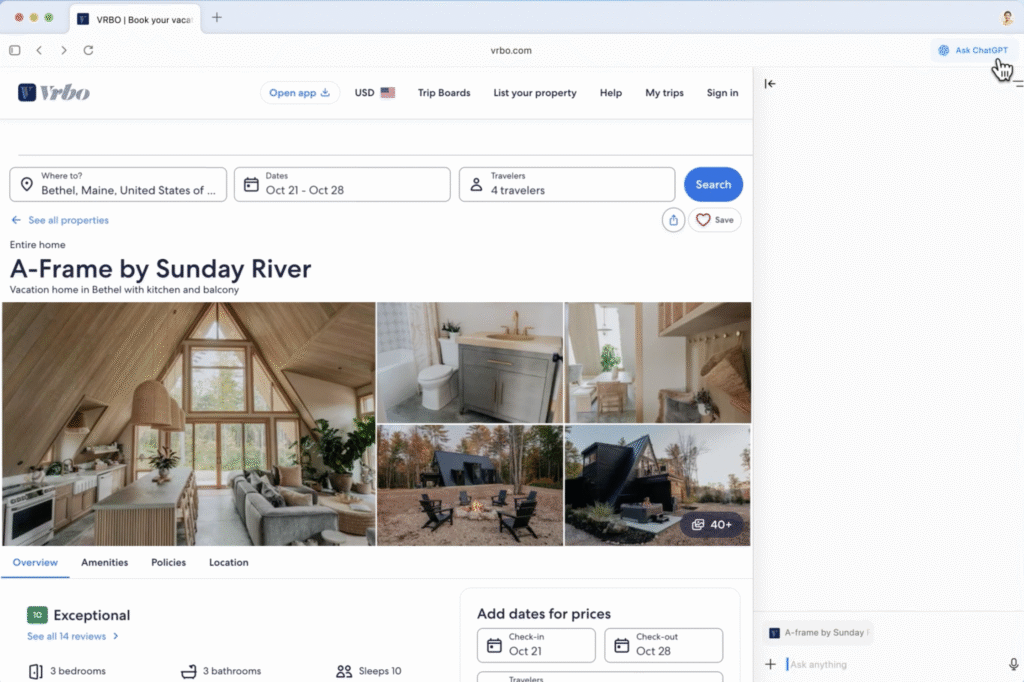

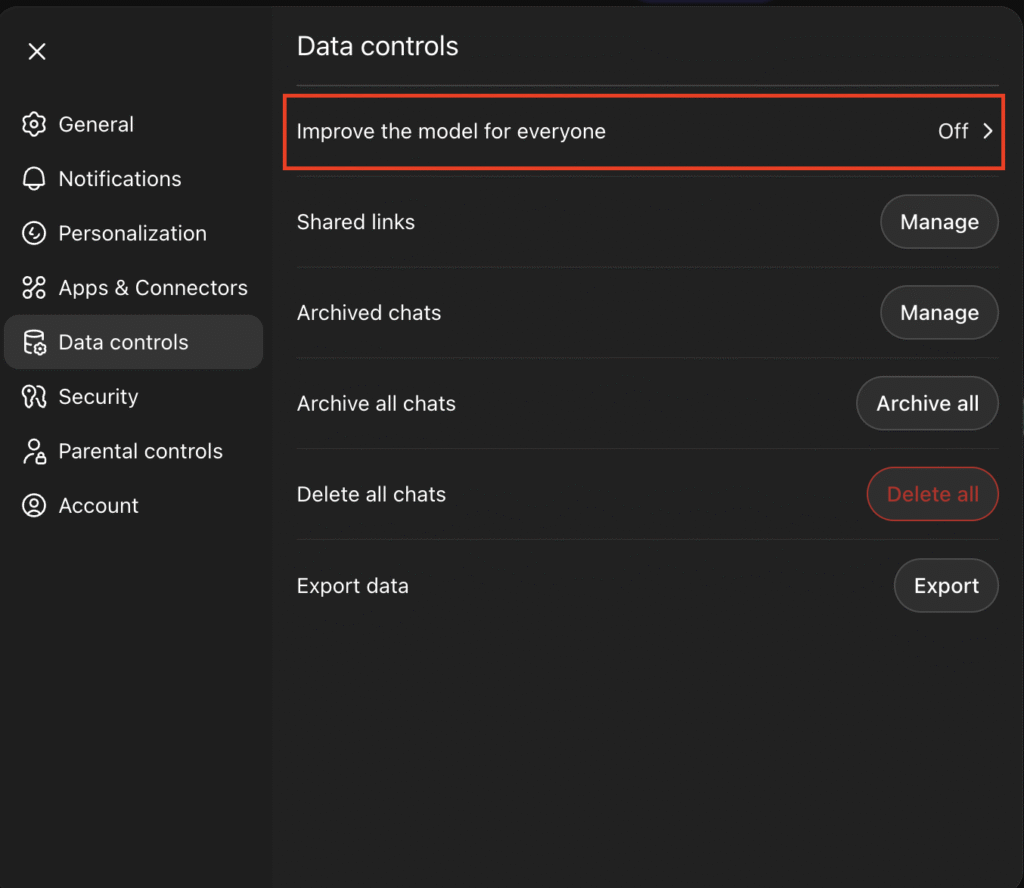

As stated on the same page, Atlas allows you to disable the “Improve the model for everyone” setting. This will prevent OpenAI from using your data to train its AI model. That said, if the same setting in your ChatGPT app is turned on, your Atlas browser will automatically follow. If you want to disable this, go to your ChatGPT Settings → Data controls and turn it off.

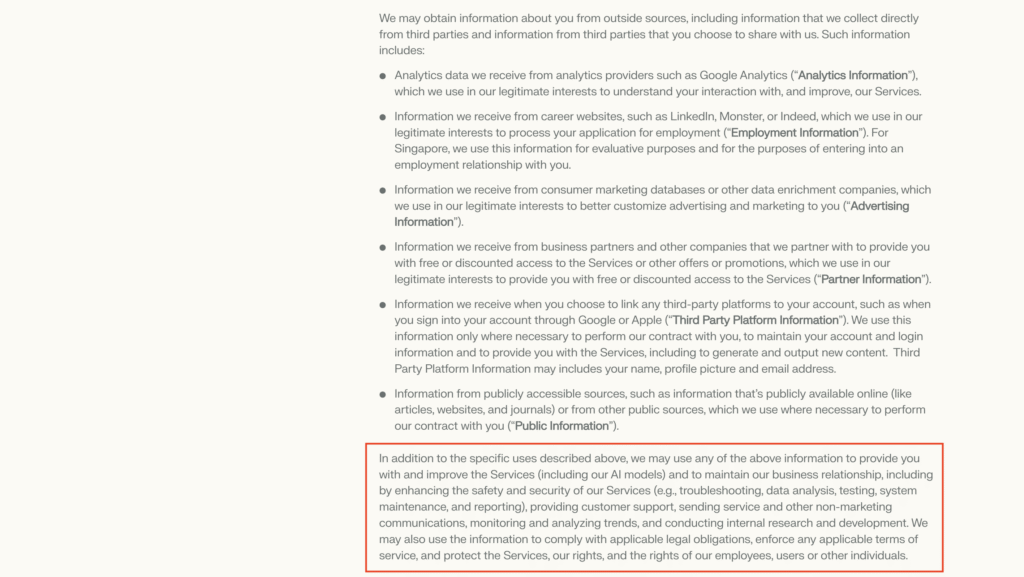

Then again, every AI browser has its own way to handle data. Perplexity’s Comet, for example, states in its Privacy Policy page that it may use some of your information to improve its services, including its AI model.

Even when an AI browser lets you delete your history, revoke permissions, or reset your profile, there’s a limitation inherent to machine learning. Once a model has been trained on your data, it can’t be fully untrained.

We’ve already seen a similar dynamic with mainstream LLMs, which are basically the powerhouse of AI browsers. Think back to early AI image generation in 2023 – the results were often distorted or inconsistent. Fast forward to 2025, and the outputs are far closer to a real image. It happened because millions of users contributed data that helped the models improve.

A deeper, longer-term trade-off is psychological. The more the browser anticipates what you want, the less you engage in the small, everyday acts of choosing, comparing, and deciding. These are the micro-skills that make up independent thinking.

Over time, heavy reliance on assistants to summarize, prioritize, or recommend can shift you from directing your workflow to following one. It’s not a guaranteed outcome, just a realistic consequence of outsourcing cognitive effort.

Conventional browsers rely on decades-old open standards created by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) or Web Hypertext Application Technology Working Group (WHATWG). This is why Chrome, Firefox, Safari, and Edge can all access any webpage.

In addition to these standard technologies, conventional browsers use algorithmic filtering to rank search results, displaying links and snippets that appear most relevant. The user then decides which sources to explore, keeping the ultimate choice in their hands.

AI browsers, by contrast, operate as a combined browser, search engine, and assistant, often summarizing, rewriting, or omitting content entirely – leaving you unaware of what was filtered or why.

For users’ convenience, AI browsers have a new layer on top of the standard web rendering that’s built on proprietary AI ecosystems, and it doesn’t follow shared rules for:

Each AI browser runs its own stack, combining a browser, search engine, and AI assistant into a single product. That means one company isn’t just helping you navigate the web, but it’s also shaping what you see, what you skip, and ultimately, what you choose.

The algorithm becomes your gatekeeper, and because its reasoning is private, you don’t know why it makes the choices it does.

And this isn’t malicious, it’s simply how answer-generating systems behave. That said, it introduces an architectural bias, where the model’s training data and internal preferences become the invisible editor of your reality.

If the AI decides something isn’t relevant, it silently removes it, creating an information bias that’s only noticeable if you intentionally double-check for that specific information. The open web becomes algorithmically filtered through a private lens.

The DeepSeek case demonstrates how this plays out in the real world. As The Guardian reported, the AI model downplayed or distorted answers about specific topics. This can be achieved by setting up an algorithm that generates a particular output.

With AI browsers, a similar scenario will occur while you browse for information or research a specific topic.

You’re probably aware that Google Chrome also collects a significant amount of your information. As Cyber Press revealed, Google gathers over 20 different data types, including your browsing and search history, device details, diagnostics, and even entries from your address book.

When you sign in and turn on sync, all your activity gets tied to your Google Account and spread across Search, Gmail, Maps, YouTube, ads – everything in the ecosystem that you consent to.

This makes sense when you consider Google’s business model. Google makes money from advertising, which depends on knowing who you are, what you like, and what you’re doing online. As Proton puts it, Chrome is basically the data collection machine engine for that system.

Yet Chrome became a dominant player in the market. This didn’t happen through coercion but by being genuinely convenient for the user base.

AI browsers follow a similar playbook by amplifying convenience even further. The difference is that the stakes are higher: they exert far deeper control over how we interact with the web and how we access information.

If an AI browser achieves similar market dominance, it won’t just shape how pages load or what ads appear. It will control how information is interpreted, summarized, and acted upon – effectively deciding what the web means for billions of users.

On the surface, AI browsers appear to collect less data than Google Chrome. And in some cases, they do. Many of them emphasize “local-first” storage, meaning your data stays on your device unless you trigger a feature that requires data processing on their cloud server.

But the thing is, AI features can’t run locally at full scale.

When you ask an AI browser to read a webpage, summarize it, analyze it, or take an action, the workflow looks like this:

So, even if you opt out of AI model training, your data still has to travel to their cloud for processing. The opt-out only limits how they reuse your data, not whether it’s transmitted.

If you ask an AI browser to automate tasks like emailing someone or scheduling a meeting, it needs access to your Gmail, Google Calendar, Drive files, and contacts to perform these actions. That deep integration is what makes it convenient – and risky.

Put simply, letting Google hold your data like a comprehensive profile builder means you have to trust its infrastructure security. By delegating your Google data access to another company’s ecosystem, you’re doubling your risk exposure.

The architectural difference between conventional and AI browsers isn’t just about features – it’s about fundamental security assumptions.

Conventional browsers build security around a document-centric model. Each website runs in its own isolated execution environment, governed by the same-origin policy, sandboxing, and user permissions.

A compromise on one domain doesn’t automatically grant access to data or capabilities on another. Even when attackers establish persistence, their reach typically stays limited to a specific site, browser profile, or device.

Conventional browsers also gate sensitive capabilities behind explicit user actions. Access to your camera, location, or payment information requires deliberate consent, constraining what malicious code can do without your involvement.

This architecture imposes friction on attackers. Exploiting conventional browsers often requires chaining multiple vulnerabilities or re-triggering malicious behavior across sessions. It doesn’t eliminate risk, but it fragments and contains attacks in ways that limit their scope.

AI browsers operate differently. They accumulate user history, preferences, and interactions into persistent memory that informs autonomous behavior across sites and sessions. Instead of treating each page as an isolated document, the AI maintains context about who you are, what you’ve done, and what you’re likely to do next.

Here’s what that means in practice: if an attacker compromises the AI’s decision-making process – through prompt injection, poisoned training data, or manipulated memory, they’re not just exploiting a single site. They’re influencing an agent that acts on your behalf across your entire browsing experience.

This shift from isolated documents to persistent, cross-domain agency creates attack surfaces that didn’t exist before.

AI browsers rely on persistent memory to store your browsing context, preferences, and history across sessions. This can transform a temporary breach into a permanent backdoor.

Researchers at LayerX recently disclosed a serious flaw in ChatGPT Atlas that exploits this exact architecture. They demonstrated that an attacker could use a Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) attack to silently inject malicious instructions directly into Atlas’s long-term memory.

As this “memory poisoning” persists across sessions, an innocent-looking link doesn’t just phish you once – it plants a sleeper agent in your browser. The next time you ask your AI to “summarize my emails” or “check my bank balance,” it could silently exfiltrate data or execute privilege-escalation commands injected days or weeks prior.

Additionally, in many AI browser designs, this long-term memory is not limited to a single device. To provide continuity across devices, user context and long-term memory are often stored in or synchronized through a centralized service.

When that memory layer is shared across devices, a compromise on one device can propagate to others, expanding the attack surface beyond a single browser instance. What begins as a localized exploit can persist and resurface wherever the AI assistant is active.

AI browsers blur the line between content and commands by interpreting natural-language input as instructions. This opens the door to indirect prompt injection.

Security investigators have demonstrated “HashJack” and similar attacks, where a malicious URL string tricks the AI into executing commands hidden in the URL fragment (the part after the “#”). Because these fragments are often invisible to server-side security filters, the AI browser reads them as high-priority user instructions.

These prompts can be encoded subtly through white text on a white background, hidden within image metadata, or buried in page comments. Researchers liken this to a modern, uncontainable version of Cross-Site Scripting (XSS), where the “script” is natural language running with the full agency of the user.

The danger lies in autonomy. A recent Carnegie Mellon University study found that when LLMs are equipped with a “mental model” of system operations, they can autonomously plan and execute complex cyberattacks without human guidance. They can simply figure out the steps on their own.

The web’s greatest strength is standardization. Standards like HTML and TLS, governed by organizations like the W3C, ensure that security boundaries are universally recognized.

AI browsers, by contrast, are built on proprietary, fragmented stacks. Every vendor defines its own “agent sandboxing” and memory logic.

While new protocols, such as the Model Context Protocol (MCP), are emerging to standardize connections, they often prioritize interoperability over security, introducing new risks, including “toxic agent flows,” where malicious data from one tool bleeds into another.

As a result, what’s considered “safe” memory in one agent may be an open injection vector in another. And vulnerabilities are essentially “black-boxed,” with no universal standard for how an agent should sanitize inputs before acting on them.

The magic of AI browsers is also their greatest vulnerability. The more we hand over control to opaque systems, the more we become passive consumers of decisions made by algorithms we can’t audit.

A 2025 survey of LLM-powered agent ecosystems underscores this systemic risk. It identified over 30 distinct potential attack techniques, spanning input manipulation, model compromise, and protocol exploits. They’re structural flaws arising from the design of autonomous agents.

Until open standards and rigorous “agentic” firewalls catch up, adopting an AI browser means trading agency for convenience.

Currently, the risk burden of using AI browsers falls entirely on you. The terms of service for these tools often explicitly absolve the vendor of liability for the agent’s actions.

For instance, the terms for Perplexity’s Comet browser reserve the right to update features or patch the software without asking for your permission.

And they state that you use the tool at your own sole risk.

At the same time, OpenAI’s Chief Information Security Officer, Dane Stuckey, has openly acknowledged that prompt injection remains an unsolved security problem that the industry still doesn’t have a clear fix for.

Critical questions regarding infrastructure, security boundaries, and open standards remain unanswered. Until the industry settles on a universal security protocol for LLM memory, these tools exist in a “Wild West” state of development.

We can’t ignore that AI browsers represent a revolutionary innovation in user experience. The ability to summarize complex threads and navigate the web through natural language is a leap forward in usability.

But, keeping in mind everything we discussed above, if you want to use them, make sure to aggressively guard your agency. Always read the AI browser’s privacy terms and data collection policies carefully before agreeing to anything.

Most AI browsers will request broad permissions to read screen content, input text, and manage tabs, as AI agents require visibility into your browsing activity to function effectively. This is the price of your convenience. If you deny these permissions, the tool loses a huge chunk of its appeal.

That’s why we recommend treating AI browsers as specialized tools, not as your daily drivers. Use them for researching public information, summarizing news, finding recipes, or navigating non-sensitive, “read-only” parts of the web where the stakes are low.

Keep using conventional browsers for banking, healthcare portals, corporate email, internal admin panels, and any site that requires a secure login. Keep your “identity” and your “agent” physically separated.

Always refrain from using AI browsers for any work-related purposes. Edigijus Navardauskas, Hostinger’s Head of Cybersecurity, advises against using these tools in professional environments due to the high probability of data leakage.

“This browser is impressive technology, but without established regulations or verified enterprise readiness, we’re essentially operating on a ‘trust me’ commitment regarding data flows. That’s not a foundation for enterprise security,” he notes.

Employees might casually paste sensitive internal data like financial documents, spreadsheets, or PII into the assistant, unaware that the data is leaving the secure perimeter. Integrated AI causes a dangerous “blurring” of the boundary between internal and external data flows.

All of the tutorial content on this website is subject to Hostinger's rigorous editorial standards and values.